20 years ago, many investors in Canada thought they’d struck it rich by investing in a company called Bre-X. Company estimates suggested it had potentially found 70 to 200 million ounces of gold at its Busang claim in Indonesia. Making it one of the largest gold discoveries ever.

Instead of reaping the rewards of being invested in the world’s largest gold mine, those investors found themselves at the heart of a massive fraud. It was eventually revealed the mining samples from the claim had been salted with gold.

To mark the occasion (and gouge old wounds) a movie ‘based’ on those events has just been released. Gold, starring Matthew McConaughey, transplants the origin of the story from Canada to the USA and moves it from the late 90’s to the late 80’s, but overall it follows a similar thread.

As always, the real-life version is a little more interesting, particularly because of the secondary stories that played out alongside the main one.

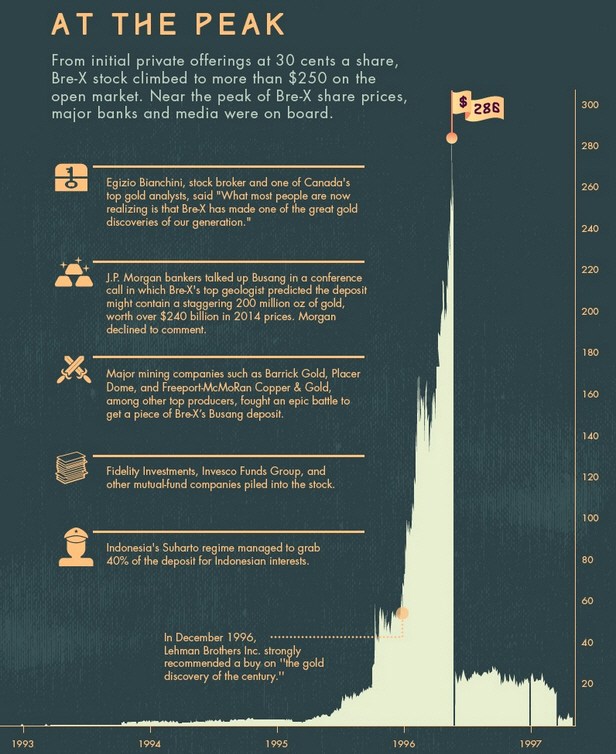

Bre-X traded on the Alberta regional stock exchange and in September 1993 it was sitting at 55 cents. Two years later it was over $15 on the back of establishing a 2.4-million-ounce resource in once section of the Busang claim and hitting good early gold strikes in another section.

One month later it was over $38 as the resource had grown to 2.7-million-ounces with the company predicting six to twelve million ounces. At this point Bre-X was generating a wave of interest from other mining companies rushing to scour Indonesia for gold claims. Canadian sharemarket investors were suddenly focused on finding “the next Bre-X”.

Take this excerpt from Canada’s The Globe & Mail from 20 February 1996.

Goldstake Explorations, a tiny, Toronto-based company with a stock that used to trade infrequently at levels around $1, pumped out a sparse 14- line press release on Friday. It seemed Goldstake had acquired what it called “a contract to work” a property on the Indonesian island of Kalimantan.

Readers who made it to the bottom half of the Goldstake release found out that lovely Kalimantan is also home to a gold property owned by Bre-X Minerals of Calgary. In fact, Goldstake pointed out that the two fields are 40 kilometres apart.

Friday’s mention of the Kalimantan property was enough to goose Goldstake’s stock from $1 to $2.35 by the time the Toronto Stock Exchange closed yesterday.

This was the Bre-X effect – speculation was enough to push a stock up 135% in a day on news a company may drill a gold claim 40km away from piece of land (not their main claim) owned by Bre-X.

This occurred across Canada’s junior mining sector and the media stoked the flames. Newspapers ran articles with headlines like “10 ways to find the next Bre-X” which included the following piece of advice:

“Good properties tend to be found by guys with checkered pasts, guys who can hustle up money,” Mr. Bianchini says. Bre-X founder had some financial skeletons in his closet — he’d gone personally bankrupt once before — but winners knew that he had the ability to identify promising properties.”

Which was true, Bre-X founder David Walsh was a former bankrupt who was initially running Bre-X out of his home. Other red flags waved high over Bre-X throughout its climb. The Indonesian government was often in dispute with Bre-X and they routinely neglected to inform the market about this fact, insiders sold millions in shares without alerting the market and gold samples had rounded edges, which Bre-X geologist Michael de Guzman explained away.

By 1996 Bre-X shifted from the Alberta regional exchange to list on the TSX, the major Canadian exchange. This afforded them more legitimacy. The media continued to focus more on the sizzling share price rather than any anomalies with the company. It soon reached a peak of $286 before a 10 for 1 split which allowed it to trade back in the $20-30 range making it more accessible to grab a piece of the company.

In early 1997, after much evasiveness and takeover attempts by major gold miners, Bre-X signed a joint-venture with the Indonesian government and one of the world’s largest miners, Freeport.

Around this time a mysterious fire in Indonesia destroyed most of Bre-X’s drilling sample records. Freeport then began due diligence on the claim – after twinning historical drill holes they found minor amounts of gold.

When geologist Michael de Guzman, flew to meet the Freeport due diligence team, he mysteriously fell to his death from a helicopter while flying over the Indonesian jungle. The red flags were finally enough and the shares crashed. It was revealed de Guzman had been buying locally panned gold to salt the mining samples. By May 1997 Bre-X had returned to penny status – under 10 cents a share.

At its peak Bre-X was worth over $6 billion Canadian and it collapsed to nothing. And when the wind came out of Bre-X’s sails, panicked investors also sold off mining companies after bidding up their shares in the hope of finding “the next Bre-X”, or just the fear of missing it.

While many people made a lot of money, many others lost a lot. Jumping on after they couldn’t stand it any longer, only to be caught out when the truth emerged.

This is the inherent problem with speculation, it’s nearly always hot air and good timing. So you need to be the very early buyer and the early seller. That’s almost impossible when most investors only hear about the next big thing when the media excitedly starts talking about it.

By then all the early buyers are exiting with their profits.